The drive through Shoshone, Idaho (pop. 1,250) on a midwinter weeknight is uneventful. The shops along Highway 26 have all closed their doors and only a couple taverns on the north side of the railroad tracks are still illuminated. The town's main thoroughfare is deserted, save for a handful of vehicles crowded around city hall, where the lights inside are glowing.

Five male townsfolk, a mayor and four city councilmen, sit on one side of a long table in the one-room city hall. They face the city clerk, a quiet woman taking notes at a desk before them. The town's police chief and its city attorney are seated to one side.

"Is there any public comment on Ordinance 425?" asks the town's mayor.

A row of metal folding chairs aligned opposite the city council are mostly empty. Only the city's maintenance supervisor and a reporter for the town's weekly newspaper have turned out for the public hearing on an ordinance regulating the size of new homes. Without comment, the city council unanimously approves an ordinance which will shape the future of the town for decades.

Something similar is happening in small towns and rural counties all across America. Local councils and school boards and commissions are deciding where roads will be built, how school will be taught, and what water will cost. Such decisions affect the day-to-day lives of their communities far more than the machinations of Congress or the changing tides of stock market trading.

As a small town newspaper reporter, I have watched rural governments match wits with deep-pocketed developers, debate the merits of public access, and negotiate contracts for sewer line improvements. These issues occupy urban and suburban governments too, of course, but their councils are often comprised of professional politicians, strangers to most of the people who elected them.

In small town America the people who elect mayors and commissioners often know the candidates by their first names and work beside them on their jobs. Many went to school with the people they choose to run their government.

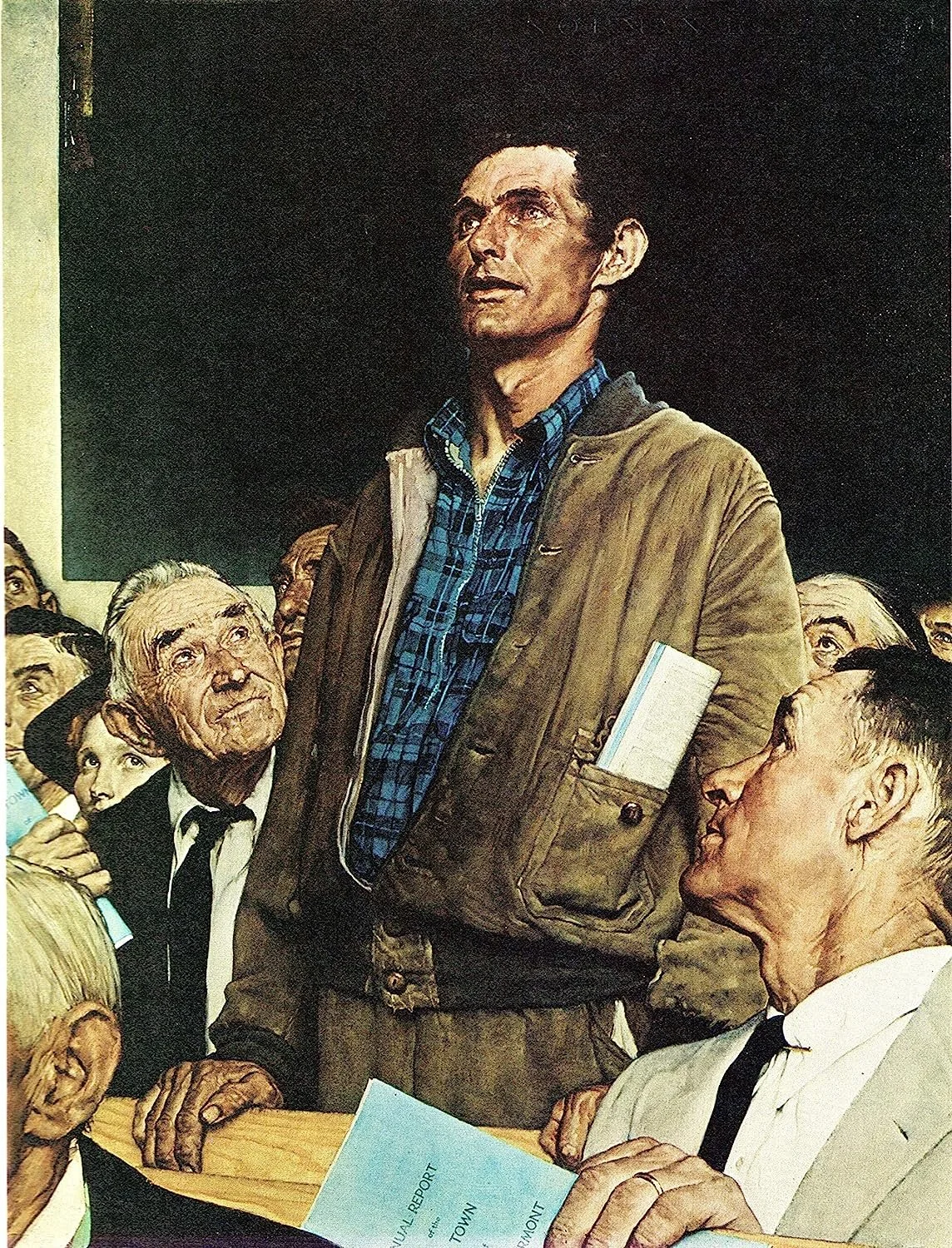

I have reported on small town elections where the outcome was decided by one vote and have often seen city council decisions swayed by the words of a single citizen. I've followed the successful grassroots campaign of a small group of country people thwarting the condemnation of public land for an Air Force bombing range and I've seen rural assemblies rally to save trees, to protest corporate crop monopolies, and raise awareness about the plight of family farmers.

There are campaigns and elections and protests before city governments as well, but there it is much harder for one voice to be heard above the din of the crowd. Elections are decided by margins of hundreds and thousands rather than by the handful. Results are less immediate and personal.

It is in the rural courthouse or city hall that the democratic principles of self-determination and representative government are most visible. Here a determined individual can affect his government. Here the citizen can elect a trusted friend as his representative.

A good friend once advised me of the three elements that constitute a full life: raising a family, operating a small business, and running for public office. Most folks complete the first two steps in that prescription with nary a thought of the third. "Politics?! That's for lawyers and celebrities. I haven't the time."

The concept of a public life as a central element in a healthy lifestyle has been greatly ignored for decades. Most Americans today are focused on their private lives and abhor public life. They do so at great cost to their communities and their own sense of meaning and belonging.

The goal of the republic, according to Thomas Jefferson, is "to make each person feel that he is a participator in the government of affairs, not merely at an election one day in the year, but every day." In that sense our national government is sadly lacking. There are few opportunities for one person to feel like a participator amid a crowd of millions. But in our small towns and rural counties the chances for involvement are much greater.

The government leaders I have known have mostly been small town merchants, tradespeople, real estate agents, retirees, housewives, farmers and ranchers. Many were driven into politics by some local issue like land use planning or street improvements. One town councilman told me how he started following local government when he and his neighbors were campaigning against plans for a subdivision development. To keep on top of the issue, he ran for a council seat and was elected, then re-elected seven times. He became instrumental in writing the town's planning and zoning ordinances.

Others become involved in government by invitation. The middle-aged manager of an eyewear shop with no prior political experience was asked to serve on a committee studying her town's parking problems. Her work on the committee led to an appointment to the planning and zoning commission. The more she learned about the town's government the more she wanted to have a voice in its policies, she told me, and after four years on the planning commission she was running for a council seat.

My own political career began with a call one evening from the chairman of the library board asking if he could nominate me for town alderman. The board was seeking more support from the town council and local libraries are a resource I cherish. I agreed, never suspecting I would win.

For those who are new to a town, or who have just recently taken an interest in its politics, it is important to familiarize yourself with the local government entities and how they operate. If your town is incorporated, it will have a city hall and perhaps a city clerk. In most towns a mayor and city council set policies and draft ordinances which are then enforced by police, firemen and other paid professionals. Ask at city hall for an agenda to the next city council meeting and inquire as to where legal notices are published. Usually the most local newspaper will carry the notices in or near its classified ads section and include coverage of public meetings in its news pages. A good newspaper can keep you up to date on public meetings and provide background on the issues being discussed.

Counties or townships are governed from a central courthouse which may or may not be located nearby. Elected commissioners govern the unincorporated rural properties and preside over county-wide services like landfills, ambulances, and weed control. Check at your town library for information on local governments, including the names and addresses of elected officials. You may want to write to them about issues that affect you.

In addition to the city and county governments, there may be special taxing districts for schools, water and sewer, recreation, hospitals, airports, fire protection, and even historic preservation. Each of these will have its own board or commission and will hold regular meetings that are open to the public. The best way to find out what's going on with any of these government entities is to attend their public meetings, which are usually held at least once a month. You may be asked what business you have at the meeting, to which you should respond, "I'm just observing."

Attend many meetings or follow local government for just a few weeks and you'll undoubtedly begin to form strong opinions on particular issues. If you want to have a voice in how they are resolved you'll have to speak out. "Letters to the editor" in the local paper are a good place to begin. Send copies to the boards or elected officials who will be making the key decisions.

Don't hesitate to call your mayor or city council member if you have an opinion to express. Or, if you feel up to speaking in public, prepare a statement to make during the next open meeting. Most government entities will make time for you at their meeting if you contact them in advance to be included on their agenda.

If you want to have a full public life and make progress on issues dear to your heart be prepared to join groups. Like-minded people will come forward or become apparent once you begin to speak your mind. You may be asked to join a special interest group, or you may want to start one yourself.

The group you join could be a political party. You may be asked to help with a campaign by distributing literature or making phone calls. Or you may be asked to run for public office.

Getting elected to a small town public office that offers little or no monetary compensation is a pretty simple matter. All you need is about a dozen signatures of registered voters on a nominating petition and a few dozen more citizens willing to vote for you on Election Day. Many offices go unopposed at the ballot box, in which case the nomination virtually ensures election.

Unlike big city elections, small town campaigns are usually inexpensive and personal. When I ran for city alderman I gave no speeches and bought no advertising. The local newspaper interviewed me and so did the radio station, but otherwise I just answered questions like "What do you want to do that for?" from the townsfolk.

My response was something like: "I believe in small town government. I think it's as close to true democracy as we get. After being an observer for a long time, I figure it's time to be an actor."

The responsibilities of public office vary tremendously. Some boards and councils meet for an hour or so once each month while others require attendance at lengthy meetings two or three times a month. When a developer proposed a massive new subdivision at the edge of our town and sought annexation there was considerable discussion at the council table and even more on the streets. Everywhere I went, it seemed, folks wanted to talk about the subdivision and what it would mean to the future of the town.

Research and preparation for meetings may take several hours, especially on complex legal issues or those involving a lot of public comment. Some people take this preparation time seriously, while others always "wing it" and vote whichever way their conscience carries them at the moment.

Getting elected to public office certainly gives you a voice in civic affairs, but it is still only one voice among several. I served on a six-member council in which I was outnumbered 5-to-1 on many issues. Without the support of at least three other council members, or two council members and the mayor, I had no hope of advancing my causes.

You don't have to be elected to public office to achieve community goals, of course. In many cases it is easier to effect change through citizen petitions and community action than it is as an office holder.

As the pastor of a small Methodist church in Monroe, Oregon, Rev. Carol Thompson appeared before school boards and city councils, wrote grants, carried petitions and organized citizen groups while helping the community combat drug and alcohol abuse in its high school. She also worked to save a nutrition program for the elderly and, most recently, developed an after-school program for elementary students.

"Rural pastors can have a great impact on a community," she points out. "You have the opportunity of influencing the decision-making process in ways you wouldn't have in a city church." The congregation in Monroe, although small, included members of the school board, city council, and other local decision-making bodies. Thompson, herself, was appointed to advisory boards and special committees that worked to improve the community.

As executive director of the Western Small Church Rural Life Center, Thompson now serves small town pastors and their congregations in 11 Western states with workshops, publications and advice on how to strengthen their rural churches. Preparing pastors for rural life is an important part of her work.

Many small towns and their churches are going through hard times, she pointed out. Young people are moving away. Older people are moving in. The ethnic mix is changing. "If you're in a community where all your young people are moving away - that's grief producing," Thompson points out.

Rural pastors, if sensitive to these things, can be of great assistance. They can help the townsfolk deal with change and create a vision for their future. They can assist their towns with improving roads, schools, parks and the community's overall spirit. "Good, quality ministry can and should happen in rural areas," Thompson concludes.

At the Center for Living Democracy in Brattleboro, Vermont, the husband-and-wife team Frances Moore Lappe and Paul Martin Du Bois direct training programs aimed at helping Americans become effectively involved in local and national politics. In their jointly authored democracy workbook, The Quickening of America: Rebuilding Our Nation, Remaking Our Lives, they describe the crisis facing Americans in the 1990s:

"The biggest problem facing Americans is not those issues that bombard us daily, from homelessness and failing school to environmental devastation and the federal deficit. Underlying each is a deeper crisis... The crisis is that we as a people don't know how to come together to solve these problems. We lack the capacities to address the issues or remove the obstacles that stand in the way of public deliberation. Too many Americans feel powerless."

Working primarily with urban and suburban residents of large metropolitan areas who feel estranged from the decision-making processes in their communities, Lappe and DuBois highlight the efforts of cities to give their citizens a stronger feeling of self-government by creating district councils and neighborhood associations. In almost every case, the "human scale" politics that are the model for effective

University of Vermont political scientist Frank Bryan and Vermont state senator John McClaughry contend that the citizens of a strong democracy cannot be "factory-built," but must be raised in a context of "communal interdependence" like that which can still be found in rural Vermont.

"Rural life is based on sociability, not estrangement -- togetherness, not distance," they write in their book The Vermont Papers: Recreating Democracy on a Human Scale. "A sense of duty is stimulated by proximity. You cannot ignore the plight of those you meet on the street every day, those with whom your family intermingles, those with whom you work and play. One acquires a habit of mutual aid."

Bryan and McClaughry advocate restoring the representative republic in America by rebuilding direct democracy based upon the model of Vermont's town meetings. Give small communities more powers of self-governance, they suggest, and the republic will right itself. Allow the centralization of power to continue and citizenship will weaken and democracy will decay.

When I learned that I had won election to my town's governing council I was stunned. It was like opening the door on a surprise party. Folks I respected and trusted, and many that I barely knew, had chosen me for a role in their government. There are precious few moments in life when you get such a public affirmation from your neighbors.

Later that night I walked down to city hall and sat for awhile on its darkened front steps, pondering the significance of the election. And that's when I remembered my friend's recipe for a full life.

Isn't it enough to make a living and raise a family?

No, not in a democracy. Our form of government depends on average citizens leading active public lives. It requires a community of individuals willing to serve on school boards and county commissions and local committees. It will not survive in the hands of celebrities and professionals, no matter how well-meaning.

Without a public life, we endanger the well-being of those we care most about in our private lives. Without a public life, we give away powers of decision-making and, ultimately, the freedoms we enjoy.