Parasites are difficult to accept. They occupy a significant niche of nature, I can grant, but their unprovoked bite and surreptitious sucking goes against my notions of decency and fairness.

What gives any critter the right to burrow beneath the skin of another and slowly drain its sustenance? As a carnivore, I can understand the need for outright killing and consuming. The food chain is linked by death. But parasites cheat the chain. They attack any potential host, plant or animal, and feed off it while it still lives. Only the eventual death of the host, usually, will stop the sponger.

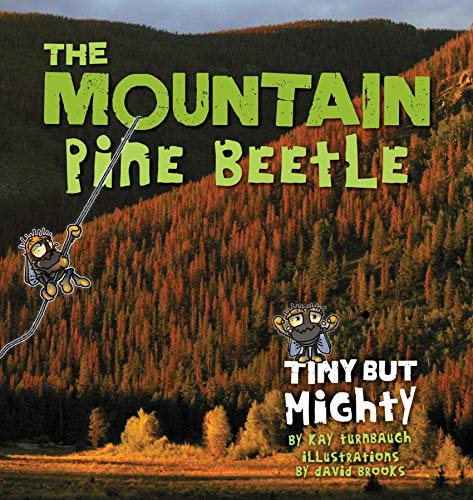

I had a tough time, then, comprehending what professional foresters mean when they call the mountain pine beetle ‑‑ a mean parasite if there ever was one ‑‑ "the creator of our forests in the northern Rocky Mountains." Parasites, to me, are harbingers of disease and death, not life and rebirth.

I was on a midsummer field trip, sponsored by a local Native Plant Society, to a lodgepole pine forest on the Sawtooth National Recreation Area in central Idaho. The day was warm and sharply scented with the pitch that oozed from several trees. The forester dug his pocketknife into one of the pouches of pitch and brought out a small black bug. "Look! We found a beetle already," he said. "That little fella destroys the tree, but begins the process that starts a new forest.”

The beetles, sometimes as many as 10,000 of them in a single tree, tunnel into the lodgepole pine and lay their eggs just beneath its outer layer of bark. The tree will bleed from the wound and sometimes "pitch out" the beetle, but more often it succumbs to the infestation. Its needles fade from bright green to dull grey and then reddish‑brown, falling to the forest floor with twigs and limbs.

The tree's corpse, the standing deadwood, will eventually fall in a windstorm or to a woodcutter's chainsaw. Or it could be consumed in one of the wildfires that sweep through these forests every 100 to 120 years.

"No beetle is as significant to a tree's life cycle as the mountain pine beetle is to lodgepole pine," said the forester. The reason is fire. Lodgepole pine cones are covered with resins that melt at temperatures from 113 degrees Fahrenheit to 446 degrees. When fires fueled by the deadwood pass through a stand of lodgepole the cones on the living trees explode, raining down seeds that will foster a new forest's growth. The mountain pine beetle, mixed with fire, is responsible for most of the forests in the northern Rocky Mountain region

The Forest Service once tried to stop the spread of beetles the way it fought to contain every fire. The only good tree was a living tree. Now that philosophy has changed. Today, fire and beetles are viewed as integral parts of Rocky Mountain forest management. Foresters accept their presence, acknowledge their purpose, and work to contain them within certain boundaries.

Like the chain of contingencies in the house that Jack built, the beetle is truly a creator. It is the parasite that killed the tree that fueled the fire that cleared the meadow and gave birth to the new forest.

Even so, it's hard to love a parasite.