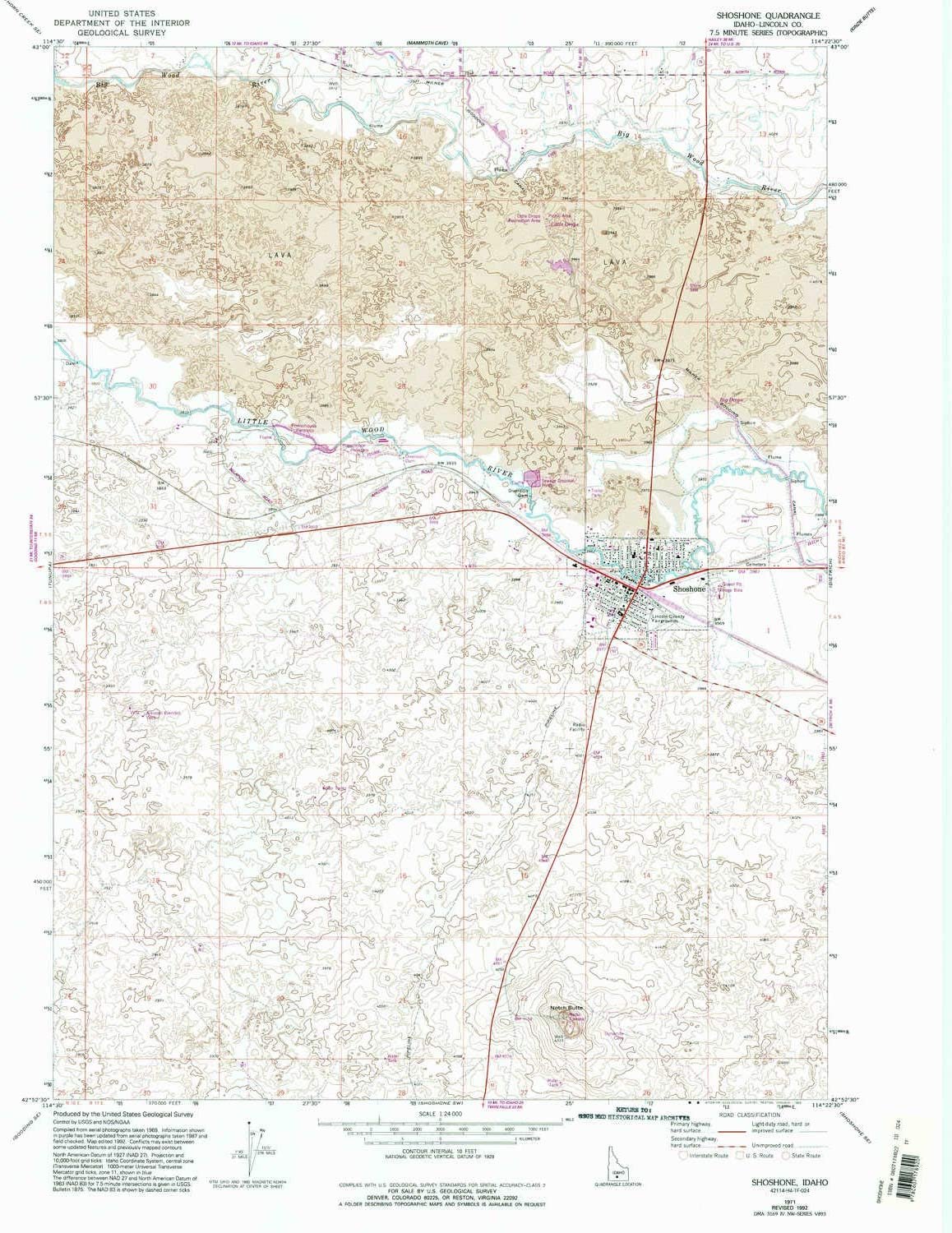

We live at the edge of the Great Rift, a crack in the earth's crust where molten rock repeatedly erupted and poured out across the plain as recently as 2,000 years ago.

This is a seemingly dry and forbidding place, with less than 10 inches of precipitation annually, where only sagebrush and wild grasses grow. But in those places bypassed by the flowing rivers of rock there are pockets of trees and cropland, like islands of green on a black sea. Wells that nourish these islands reach deep below the lavas to draw from an immense aquifer that stretches to white-capped mountains to the north and east.

My mother-in-law, who has grown accustomed to suburban amenities, thinks we live at the end of the earth. What possesses us to live in such a place, she wonders.

Possession. That's a good word for it.

Some folks reside in a particular place by chance, whether by birth or employment, and have little ambition or opportunity to go elsewhere. Others live rootlessly, carried from place to place by the winds of fortune, unaffected by the change of scenery.

Most interesting, however, are those people who feel drawn to a certain geographic location, compelled to settle down in a particular microclimate, attracted to some grove of trees or angle of the sun, possessed by how a place smells, or feels, or looks at a certain hour of the day.

In her book, The Place Within, editor Jodi Daynard commissioned 20 writers to prepare essays on the places most particular to them -- home, if you will -- and how those places have shaped or influenced their lives. Some wrote about urban domains like Manhattan and San Francisco and St. Louis.

Phillip Lopate found that "growing older means losing Manhattan -- or the El Dorado it has signified." New York, like most U.S. cities, is a good place to be young and full of restless energy; it does not serve so well as a home.

Ellen Meloy took her youth to Montana, hoping that the state's "humbling and informing scale would provide the proper vessel for my terminal restlessness, my notion that home could be found in movement itself. I felt that rootlessness might find root in a place of this size." Like Gretel Ehrlich, who writes about sheep ranching in Wyoming, she had not planned to stay so long, but couldn't make herself leave.

For some folks the baldness of the Great Plains, so devoid of trees and hills, holds no attraction. Others find solace and meaning, as Kathleen Norris reveals:

"The immensity of land and sky in the western Dakotas allows for few trees, and I love the way that treelessness reveals the contours of the land, the way that each tree that remains seems a message bearer. I love what trees signify in the open country."

The Place Within also includes William Kittredge's reflections on eastern Oregon, Harry Crews' stories about the Okefenokee Swamp in south Georgia, Alan Lightman's experiences on a remote island off the coast of Maine and Donald Hall's portrait of New Hampshire in winter.

Off all these writers, no two share similar places or even common opinions about the landscapes that obsess them. What calls people to a place is as diverse, it seems, as the places they are called to and the complexity of human nature appears made to match the complexities of the earth's landscapes.

We love our place for its open sky framed by mountains; we cherish its stillness, the steady progression of its seasons, and the almost everpresent sunshine.

We've lived in many other places, large and small, and have enjoyed some stunning views. Had we chosen from some almanac or followed public opinion, we might have selected some other place. But once we saw this one, we knew it was our place.