During the 18th century, a new invention known as the flush toilet, or water-closet (WC), became increasingly popular. The handy chamber-pot kept in the sideboard was no longer socially acceptable. Paradoxically, however, this sanitary "improvement" made London more dangerously polluted than ever before.

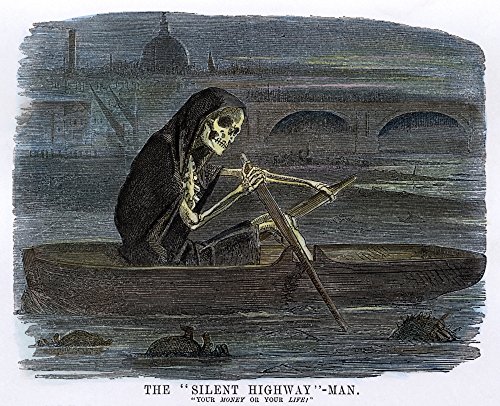

The new WCs were so arranged that they discharged into old cess-pits, which consequently overflowed into the surface water sewers beneath the streets. As these had been earlier designed to collect rainwater only, and to discharge into the rivers and ditches connected to the Thames River, the improved domestic arrangements unaccompanied by improvements in the sewerage system brought London to the verge of disaster, a giant step forward for personal hygiene and two steps backward for public sanitation.

Much of London's drinking water was being extracted from the Thames, in many cases downstream from the sewage discharge points. But the disorganized state of London's administration frustrated all attempts to deal with the growing problem. There were no less than eight independent Commissioners for Sewers at the time, each concerned only with their own districts.

The event which pushed London's legislators into action was the 'The Great Stink' of 1858, when the combination of an unusually warm summer and an unbelievably polluted Thames made the stench from the river so bad that Members of Parliament fled from the rooms adjacent to the river and Benjamin Disraeli rushed from the debating chamber, handkerchief to nose.

"There was no shortage of plans for the safe, efficient, and tolerable disposal of the city's waste, but any undertaking of an appropriate magnitude required an unprecedented mobilization of political will, technical expertise, and material resources," writes David S. Barnes in Filth: Dirt, Disgust, And Modern Life.

The pungency of the stench was catastrophic, Barnes continues, "not a gradually developing, unpleasant sensation but a devastating and even incapacitating onslaught. The stench was intolerable... While sanitation workers dumped tons of lime into the river in a desperate attempt to counteract the stench, sheets soaked in chloride of lime were hung over the windows of the Houses of Parliament. MPs finally understood on a visceral level that something had to be done."

Disraeli introduced to Parliament a Bill which gave engineer Joseph Bazalgette the authority to construct a system of intercepting sewers which he had designed and proposed earlier, but which had been held up by government bureaucrats. The Bill passed into law within sixteen days and Bazalgette began work immediately.

Over the next sixteen years Bazalgette built 82 miles of main intercepting sewers, eleven hundred miles of street sewers, four pumping stations and the two treatment works at Beckton and Crossness which Thames Water still operates. The system has been extended and updated as London has expanded and Bazalgette's huge steam pumps have been replaced by modern electrically powered systems at Beckton and Crossness, where Bazalgette's magnificent buildings are being restored by the Crossness Engines Trust.