by Michael Hofferber Copyright © 1995. All rights reserved.

On a golden afternoon in early autumn I return to a mountain lake I've visited many times over the years, dating back to when I was a child at summer camp. Some sense of connectedness brings me back, time and again, to reacquaint myself with familiar waters and old recreations.

Each time I rent an old 15-foot Grumman at the marina and paddle, somewhat aimlessly, along the shoreline. The rhythmic lapping of water against the hull and the far-off cries of loons float atop a deep and peaceful quiet. Blue skies are mirrored on the smooth surface, where anything that moves produces a sparkle and, then, dimpling circles of ever wider and fainter proportion.

Sometimes I'll drop a line for trout or scramble ashore to look for frogs or driftwood. Mostly, I linger in private coves scented by bordering pine trees and watch for deer emerging from the shadows or osprey soaring overhead.

Canoeing appeals to many moods and ages. For me, it's been at various times a source of childhood adventures, fun-filled family outings, and quiet retreats from day-to-day business. It's as much a sport for boys as girls, and as easy for Grandma to master as it is for a burly truck driver.

Some folks, like myself, canoe the flat waters of quiet rivers and calm lakes. Others lean toward the challenges of fast and roaring whitewater. Whatever your preference in this self-propelled sport, there is a canoe to match your ambitions.

The word "canoe" derives from "canoa," a Carib Indian word recorded by Columbus meaning dugout. Many Native Americans crafted canoes from hollowed out logs -- dugouts -- or by using birchbark or hides stretched across a wooden frame.

European explorers, fur-trappers and missionaries became enthusiastic canoeists, paddling and portaging their craft for hundreds of miles across unfamiliar territory. The canoe was as essential in the backcountry of the 17th and 18th centuries as four-wheel-drive vehicles are today. It could be maneuvered down narrow channels or across broad lakes with similar ease, and if a man had to he could carry it across land. Try that with a Land Rover!

Canoes of the late 20th century are made of synthetic woven fibers instead of hides. Plastic resins and thermoplastics have replaced most wooden frames. The modern canoe is lighter, tougher and faster than its colonial counterpart. An average person can lift many of them one-handed.

Not all canoes are the same, of course, and there are almost as many styles as there are uses for the craft. Recreation canoes are best for leisurely paddling or fishing on calm waters. Their hulls are wide and they have a flat bottom that gives them extra stability. These are the canoes rented at most liveries and resorts, designed to safely carry families as well as sportsmen.

Touring canoes are a little longer (16 1/2 to 18 feet) and wider with a slightly rounded bottom. Built for longer trips across rougher water, they'll carry more gear and maneuver more easily than the recreational models.

Cruising canoes are designed for experienced canoeists who want more speed. These canoes are about 18 feet long and have a shallow V-shaped hull that delivers more speed and distance per paddle stroke than the recreational or touring models.

Other types of canoes include wilderness-tripping canoes for long-distance travel, whitewater canoes for negotiating rapids, and downriver canoes for racing. All of these are built for veteran canoeists who know their strokes, not the novice or weekend paddler.

Out of the water, most canoes transport rather easily. There are handy loading devices available for stowing canoes atop vehicles or trailers. The top of a fold-down camper can also be outfitted to hold a canoe.

Paddles and life jackets are essentials that will be provided with any rental canoe, but if you buy your own craft you'll have to select these separately.

A canoe paddle is not the same as an oar, which is usually longer and designed to be inserted into an oarlock in the side of a rowboat. Paddles are unattached and meant to be held with two hands, one on the grip and the other on the throat leading to the flat blade. Varying in size, weight and material, the choice of a paddle is largely personal preference. Whatever feels good is best, but the shape of the blade can make a difference in maneuverability and novice or recreational canoeists should look for a beavertail (long and narrow like a beaver's tail) shape approximately 5 to 7 inches wide and 14 to 20 inches long.

Life jackets are called Personal Flotation Devices (PFDs) by the U.S. Coast Guard, which sets flotation standards that approved products must meet. The PFDs that come with many rental canoes are the uncomfortable horse collar type that fit over the head and tie across the chest. More popular among canoeists are vest-type PFDs that look and wear like down vest jackets. Whichever is used, make sure the size of the PFD is sufficient for the person inside.

The only other accessories needed to start canoeing are drinking water, a bailing bucket and sponge for removing water from inside the canoe, a 20-foot length of rope called a "painter" which is attached to the front end and used to tie up the canoe when going ashore, and muscle power.

Paddling is actually easy to learn and not as strenuous as it might seem, especially on calm water. By trial-and-error most first-time canoeists quickly learn that paddling on the right side of the canoe makes it veer left, and paddling on the left side makes it veer right. Only by paddling on both sides alternately, it seems, will the canoe travel in a relatively straight line. But by turning the paddle away from the canoe at the end of the stroke the push-away movement will correct the veer and keep the craft going straight ahead.

There are other tricks to paddling solo and in tandem, like using back strokes to brake your speed or a bow rudder stroke to turn sharply with little effort. These are taught in canoeing classes, schools and clubs in many communities. But no one should let the lack of formal training dissuade them from going canoeing on a calm lake or gentle river. The basic skills of the activity are like riding a bicycle -- quickly learned and rarely forgotten.

Canoeing may involve long trips through wilderness areas or quiet moments on local lakes and rivers. Splendid opportunities for paddling are available in almost every state and the mobility of the canoe allows access to quiet, scenic sites far from crowded campgrounds.

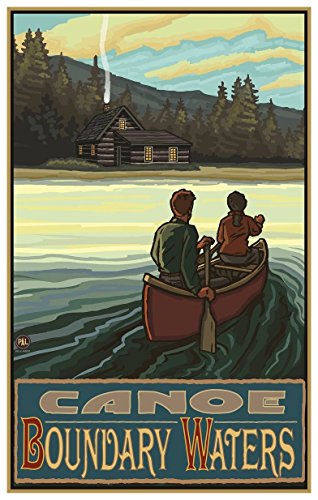

There are a number of U.S. waterways famous for their canoeing like the Boundary Waters Canoe Area of northern Minnesota, the Allagash and St. Johns Rivers in northern Maine, the Ozark National Scenic Riverway in Missouri, and the Delaware River between Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Professional outfitters are available in these areas to plan, equip and guide your journey. Or you might join an outdoor organization that sponsors wilderness trips led by experienced volunteers. Information on outfitters and canoeing clubs is available from the American Canoe Association, P.O. Box 1190, Newington, VA 22122.

Wherever you choose to paddle, the best advice anyone can offer is to go easy and follow your own interests. Canoes are like pickup trucks, reliable vehicles for those who know how to drive and appreciate them. Whether it's a family picnic on a secluded island or a hunting expedition in the backcountry, the right canoe can get you there.

For myself, I am happy for some stolen moments on a quiet lake or meandering stream, fancying myself akin to the aboriginal Indians or some intrepid trapper. Sometimes I'll sit back, paddle at rest, and drift with the wind while listening to the plop of rising fish, the squawk of waterfowl and the pee-yeeps of tree frogs. I'll have found my destination, then, and reached it by canoe.

Other Options