On certain dry plains and hillsides of the West, the Astragalus species of wildflower grows in abundance, spreading carpets of pea-shaped pink, purple or yellow blossoms across the arid landscape. The delicate colors and innocent-looking nature of the plants belie a deadly disposition.

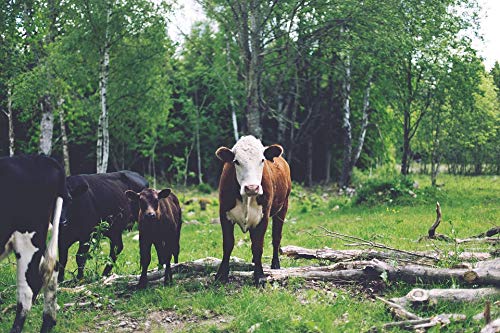

Astragalus, more commonly known as "locoweed," thrives on soils rich in selenium, an element toxic to people and animals in high doses. Locoweed absorbs selenium and passes it along to livestock that graze on its bushy leaves, causing the infamous "loco disease" that has decimated many herds.

Irrigation water also picks up selenium as it moves through soils rich in the element, which is what happened in California's San Joaquin Valley in the 1980s when irrigation discharge emptied into the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge.

"Laced with dissolved salts and minerals, the tainted drainage was a lethal brew. Too saline to leave in the fields, it was being dumped into Kesterson as part of an experiment to convert pollution into providence," writes Tom Harris in Death in the Marsh, his account of the disaster that followed in the mid-1980s.

Within a few short seasons wildlife biologists began to notice terrible changes in Kesterson's wetland ecosystem. The marsh's vegetation was dying back and fewer fish, birds and animals were being counted. The nests of waterfowl that once held chirping nestlings now yielded many stillborn embryos and, worst of all, chicks with hideous deformities like missing legs or wings, external stomachs, and twisted beaks.

Death in the Marsh details the nightmarish discoveries at Kesterson and traces the scientific search for the source of the problem with selenium, which has been alternately studied and ignored for nearly a half century.

The livestock die-offs that early-day ranchers in the West attributed to "alkali disease" may have been selenium poisonings, according to Harris.

"It wasn't until the early 1930s that researchers began to pin down the evidence that it was not the mineral salts associated with the prairie's ubiquitous alkali crust that were doing the poisoning, but selenium," Harris explains.

As an environmental reporter for the Sacramento Bee, Harris covered the Kesterson story and led an investigative report on evidence of similar problems throughout the West. With fellow reporter Jim Morris, he surveyed other federal water projects in nine states in 1985 and found potentially dangerous levels of selenium at all of them, including Idaho's Lake Lowell near Nampa.

Dave Carter of the USDA's Agricultural Research Service office in Kimberly, Idaho, said he knew of no reported toxicity problems with selenium in his state, but admitted that the potential exists.

"Wherever we have a lot of seepage water there is potential for selenium concentrations to build up," he said.

More common in southern Idaho, with its extensive layers of lava formations, is selenium deficiency. Livestock, like humans, require small amounts of selenium in their diet to remain healthy. Without it, they may lose weight and hair.

"Selenium deficiency has caused, and continues to cause, a lot of economic loss in Idaho," Carter pointed out.

For many years, livestock in Idaho were vaccinated with selenium to prevent deficiencies, he noted. Now selenium is commonly applied to alfalfa fields with fertilizer in small amounts, increasing the selenium content of crops.

Harris' book suggests that human health can be endangered by inhaling the selenium dust in feed or fertilizer additives, eating plants and animals harboring excessively high levels of the substance, or drinking selenium-tainted water. He cites the example of Burns, Oregon, rancher Girard Perkins who wasted away and died from a mysterious disease in 1972-73. Selenium counts in the man's organs were among the highest ever detected in a human, Harris reported.

How did Perkins get so much selenium in his body?

"One theory is that Perkins came across just one tainted batch of pothole water too many," according to Harris. "Like the cowpokes of an earlier generation, when he was out on solitary range rides, checking his herd, he would quench his thirst by scooping his Stetson into one of the numerous ponds, creeks, or seeps that dot the undulating plains."

According to Dr. Sandra Susten of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) in Atlanta, Georgia, there have been no reports of populations in the U.S. suffering from selenium poisoning.

"There's evidence, though, that some workers might be hypersensitive to selenium," she said.

The symptoms of selenium poisoning are much the same as the symptoms for selenium deficiency: brittle hair, deformed nails, loss of feeling and control in arms and legs (in extreme cases).

Selenium, Harris's book points out, is one of the least understood and least regulated of the toxic elements -- five times more poisonous than arsenic. It underlies thousands of square miles of North America and affects the livestock that graze, the crops that grow, and the people that live on its surface. But few are aware of its presence or the dangers that it poses.

Death in the Marsh raises plenty of alarm, but offers few solutions. Selenium has helped shape the landscape of the West since at least the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago. Animals have grazed upon its surface and people have dwelled near it since the last Ice Age. How did they survive its poison? Is it the massive federal water projects of this century that made selenium a threat? Or has tainted water always been a consequence of irrigation?

In his epilogue, Harris acknowledges the gloominess of his report. Selenium is so widespread in the West and its effects so poorly understood, he writes, that the chances for constructive change are daunting. Only a coordinated and well-funded program of research and intervention, Harris suggests, will reduce the threat to livestock, wildlife and human lives.