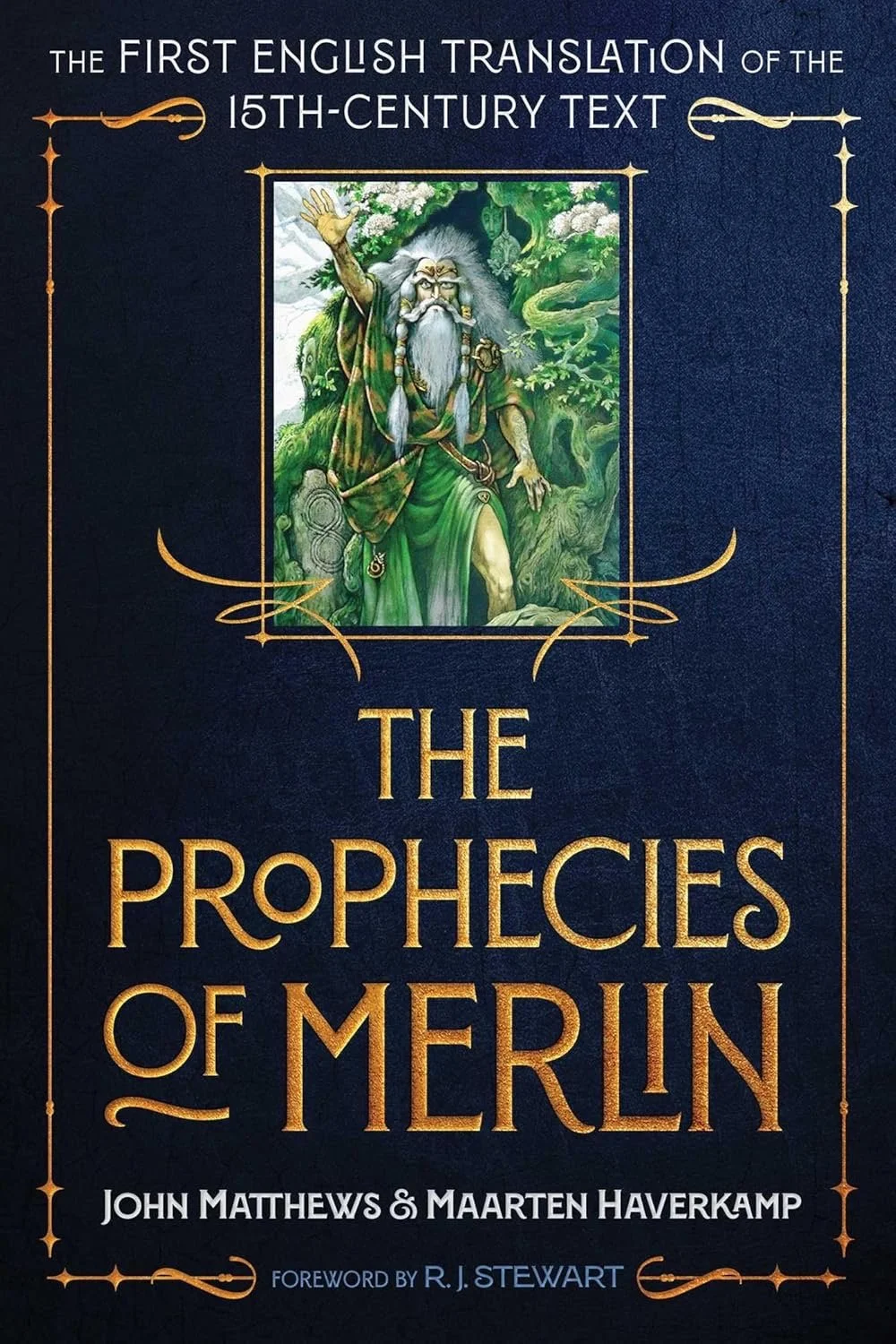

In their book The Prophecies of Merlin: The First English Translation of the 15th-Century, authors John Matthews and Maarten Haverkamp claim to have acquired a French book from 1498 titled “The Prophecies of Merlin” that was a compilation of documents collected by an unknown 13th century monk. They say they spent five years translating the mysteries hidden in this obscure book and are now presenting its first English translation with commentary, sharing forgotten stories of early Arthurian literature and magic.

The book reveals forgotten Arthurian lore, including stories of Merlin’s demonic birth, his supernatural abilities from infancy, and his survival against threats as a child. And it details Merlin’s affair with the Lady of the Lake and his ultimate imprisonment, stories of Percival’s first contact with the Grail, and King Arthur’s ties to the mystical Prester John.

Included are early Welsh prophecies attributed to Merlin, others compiled by Geoffrey of Monmouth, and references tothe famous Letter of Prester John that inspired explorers like Columbus. The commentary explains the historical significance and esoteric symbolism, attempting to “breathe new life” into forgotten Arthurian prophecies and magic traditions.

The authors assert that they are sharing “virtually forgotten and, to date, untranslated” stories, positioning their work as both a scholarly feat and a contribution to the Arthurian literary tradition.

The historical claims made by Matthews and Haverkamp connect to a complex tradition of Arthurian “Merlin Prophecies” that are indeed attested in medieval French literature, but not exactly as presented in their book.

There is scholarly consensus that a French prose text called Les Prophecies de Merlin was composed near the end of the 13th century that combines both Arthurian romance and contemporary political prophecies. Over 20 manuscripts exist, with the earliest known from 1303. Later printed or compiled editions may have appeared, such as one dated 1498, but these are derived from much earlier sources.

These Prophecies are not a single, unified text but a patchwork of materials that drew from prior prophetic traditions, particularly those associated with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 12th-century Latin Prophetiae Merlini, as well as locally relevant political commentary from later medieval Italy and France.

As for the existence of a specific book titled “The Prophecies of Merlin” from 1498, references indicate that such a printed book may exist or has existed, reportedly acquired and translated by Maarten Haverkamp. However, no independent bibliographical or archival evidence is currently available in scholarly databases that would authenticate the originality, continuity, or unique content of a 1498 edition as described by the authors.

So, while the Prophecies of Merlin are real medieval texts, the specific historical details and uniqueness of the 1498 book claimed by Matthews and Haverkamp have not been independently verified or substantiated in academic sources. Their version draws on authentic traditions, but the claim of rediscovering wholly forgotten material or a unique compilation lacks supporting evidence from authoritative medieval scholarship.

Likewise, there is no historical evidence supporting Merlin’s prescient abilities as literal fact; these abilities are literary constructs found in medieval texts that helped define his legendary status. Claims of Merlin’s prescience reflect the medieval fascination with prophecy rather than evidence of supernatural foresight. There is no corroboration from contemporary records or scholarship for Merlin’s prophecies as historical fact.